Our Street Fighter history series continues with a look at the time Capcom tried to start over

In the mid-’90s, Street Fighter 3 was a mirage. After Street Fighter 2 blew up, a numbered sequel was inevitable, yet — following more than a dozen upgrades and spinoffs — it was nowhere to be seen. For six years, in the absence of genuine news about sequel plans, fans drank the sand, latching on to whatever rumors and gossip they could find.

“Here’s the exclusive first news on Street Fighter 3,” wrote Diehard GameFan magazine in its April 1993 issue, as teased on the cover.

“This new version will incorporate only two of the original cast from part two, Ryu and Sagat. You know what that means… 14 new characters! Now, when Ryu does his fireball, he has an aura around him, and Sagat can now do a tiger knee helicopter kick. Instead of 3 special moves per character, there are now 5, and there is no more lag time after throwing a fireball, you can now automatically connect it with a dragon punch. And there’s no more charging to do moves like Guile’s sonic boom or Blanka’s spinning ball from part 2. There will also be one command that all the characters can use. As far as new characters, we know about two so far, Chun Li’s younger sister, and Bison’s mentor (who will be the last boss), his name is Shadow Lu. Street Fighter 3 is only a working title (even the name may change). This new game will incorporate two new 16 bit processors created by Capcom, which will be running parallel to each other (parallel processing). We’ll have more info for you next month and maybe a big surprise. Remember you heard it here first.”

On the Usenet newsgroup alt.games.sf2, players posted prank links promising nonexistent screenshots and test site details.

At a Software Etc. in Torrance, California, employees signed customers up for imaginary pre-orders.

Throughout magazines like GameFan and Electronic Gaming Monthly, reports and rumors circulated that the game would have 3D graphics, that it might be developed in the U.S., that it would run on Nintendo’s Ultra 64 arcade hardware, and that it would be exclusive to Nintendo’s next home console.

In arcades around the world, players told the same joke: “Can’t Capcom count to three?”

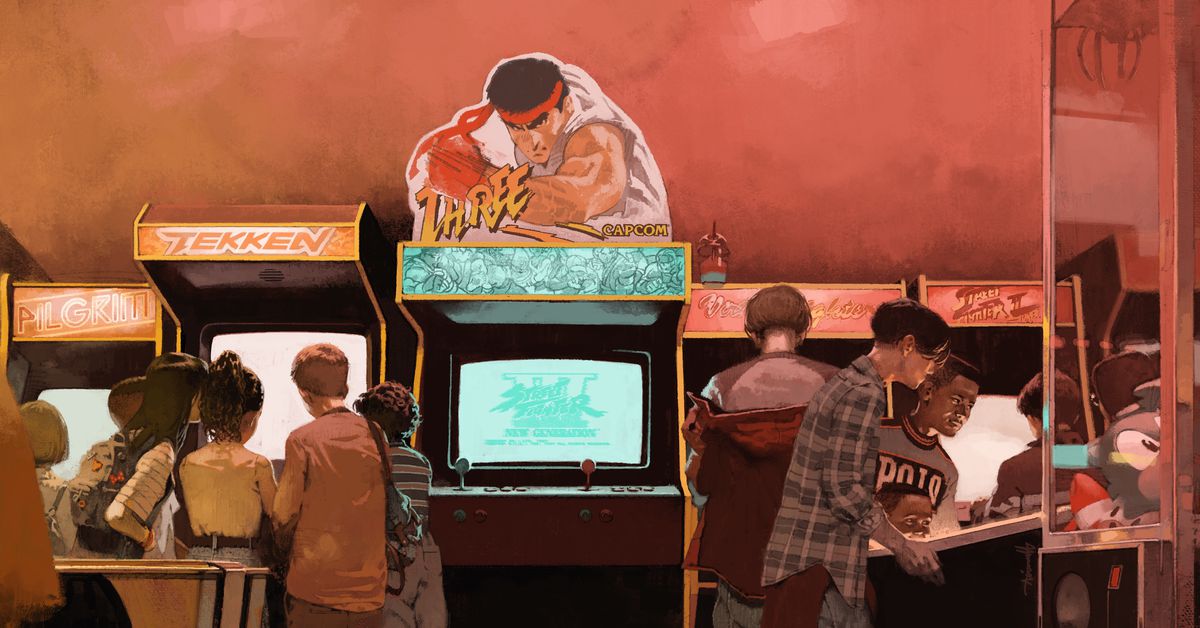

As the second game released on Capcom’s CPS-3 arcade hardware, Street Fighter 3 features 2D visuals that arguably haven’t been topped since, even 20 years later.Graphic: James Bareham/ProSpelare | Source images: Capcom

Six years later

As it turned out, for about half of that six-year stretch, Capcom had been working on Street Fighter 3 — it just hadn’t told anyone.

In 1997, Capcom released Street Fighter 3: New Generation, showing its work by underlining the word “Three” front and center on the game’s arcade marquee.

Flying in opposition to market trends and most of the circulated rumors, Capcom delivered a 2D game with highly detailed art and animation — which led to many calling it one of the best-looking 2D games on the market. The development team made subtle changes to the series’ mechanics, added a parry system that allowed players to counter attacks, and took a bold chance by wiping clean the character roster, only bringing back series mainstays Ryu and Ken.

As quickly became clear, the market Capcom entered in 1997 was far different from the one it had dominated in 1991.

Noritaka Funamizu

(Street Fighter 2 series producer, Capcom Japan)

Street Fighter 3 was the point when I said I would no longer do this. I think I’d just been so involved in the Street Fighter series that Capcom initially assumed, Yeah, you’ve got to make 3 as well. I said no. […] At that point, I just wanted to make my own game.

Chris Kramer

(Street Fighter series public relations representative, Capcom USA)

At that point, the Street Fighter brand was kind of in a rocky place. You know, sales hadn’t been good on home versions. The U.S. arcade market was dying. And everybody was looking at what was happening on PlayStation and Saturn. They were like, OK, 3D games — this is the future. And Capcom was leaning in way hard on traditional 2D animation with Street Fighter 3. So it was like, OK, this looks great, but it also looks like more Street Fighter.

Akira Yasuda

(Street Fighter 3 artist, Capcom Japan)

Virtua Fighter had already come out by that point, right? I mean, there was no way 2D graphics could win against that. If we were going to beat Virtua Fighter, we had to make something that would go down in the annals of gaming history. I knew it was a battle we weren’t going to win, but we had to fight it anyway.

Matt Atwood

(Street Fighter 3 public relations manager, Capcom USA)

Virtua Fighter and Tekken were the big ones, and they were tough because it was something different. There was a significant group of people who loved Street Fighter that were also like, What’s next in the category? […] It felt like, from a promotional standpoint, how can we compete?

James Chen

(Street Fighter series commentator)

I still remember, and this used to make me so mad when I was younger, the magazine reviews would come out and like […] you had to be 3D or people thought your game was ugly. […] It was like, Wow, they’re really sticking to this, huh? Even despite how beautiful the game animation was. But 3D — even the freaking PlayStation 1 ugly polygon kind of stuff — was the thing at the time. And so yeah, a lot of people were disappointed that it was sprite-based, because 3D was such a fad at the time.

Noritaka Funamizu

(Street Fighter 2 series producer, Capcom Japan)

Street Fighter 3 was always intended to be a 2D fighting game that would take 2D to its limit, and home in on the 2D aspect. And part of the idea was it was going to be made by a new generation of creators, so I think, for both myself and for Yasuda, we felt that we didn’t want to say anything that would interfere with the direction of the new generation.

Akira Yasuda

(Street Fighter 3 artist, Capcom Japan)

It’s a bit of a complicated story, but [Tomoshi] Sadamoto, the director of The King of Dragons, initially conceived of making an original fighting game that wasn’t part of the Street Fighter series.

Shinichiro Obata

(Street Fighter 3 planner, Capcom Japan)

Yeah, that’s true. But it was only an original game at the very beginning of the project.

Takayuki Nakayama

(Street Fighter 5 director, Capcom Japan)

The project was operating under the title “NEW GENERATION,” which [later became Street Fighter 3’s subtitle]. This was also written on the project binders at the time. When the project began, neither Ryu nor Ken were included.

Akira Yasuda

(Street Fighter 3 artist, Capcom Japan)

I remember seeing the initial concept of Sadamoto’s game and thinking, You know, they’re probably going to want to turn this into a Street Fighter game anyway. The characters didn’t seem to have a lot of personality, so I proposed that they add Ryu and turn the game into a Street Fighter game. […] At the time, there were team members who weren’t really open to or supportive of that idea.

What took so long

Capcom kicked off Street Fighter 3’s development in 1994 — originally as a new IP — using a small team led by producer Tomoshi Sadamoto. The team expanded in 1995 as more staff became available, yet it took until early 1997 for Capcom to ship the game to arcades — an anomaly at a time when most of Capcom’s fighting games took a year or less to develop, and a counterpoint to the fast-tracked Street Fighter Alpha.

Street Fighter 3 was to be a showcase of Capcom’s technical abilities and new CPS-3 arcade hardware, with extensive resources poured into the game’s 2D visuals. But as planner Shinichiro Obata says, that wasn’t the only reason the game took so long to make.

Shinichiro Obata

(Street Fighter 3 planner, Capcom Japan)

After working on [vertical scrolling shoot-’em up] 19XX, I was trying to figure out what kind of project I should do next, and my boss at the time, Funamizu, asked me to try designing a new kind of shoot-’em-up. But it just so happened that at the same time, Street Fighter 3 had already been in development for two to three years, and, just honestly speaking, it wasn’t looking very interesting, and I didn’t think the team was making good progress with the title. There also weren’t enough game designers on the team, so I ended up joining the team in order to help them. […] More than two years had passed, so the game was in its third year of development.

To explain what happened, there was a big structural change at Capcom at the time. Prior to that point, the company didn’t have a system where a different producer led each project. [Capcom head of development Yoshiki] Okamoto had been producing pretty much every game Capcom released. But then Capcom solicited the services of a consulting company that recommended Capcom introduce a producer system in order to streamline the flow of development. […]

So when that change happened, the people who had been the lead game designers or directors ended up becoming the producers of Capcom’s projects. In the case of Street Fighter 3, it was originally spearheaded by someone who worked on it as a lead designer or director, and then he became the producer. But the thing is, a lot of these people had only done game design, so they didn’t know how to produce games. And when he became the producer, Capcom had to find someone to take his place as the lead designer, and they assigned that job to someone who was pretty junior at the time.

The thing about Street Fighter 3’s team was that, surprisingly, even though it was Capcom, which was known for fighting games, 70% to 80% of the team members had no experience making fighting games. Why that was the case, I honestly have no idea. But there were people in the team who were quite inexperienced. I think more than half of them — mainly the planners and programmers — weren’t really familiar with fighting games at all. By this point, a lot of the old guard, the people who had worked on fighting games beforehand like [Street Fighter 2 co-planner Akira] Nishitani, had already left the company. And even amongst those of the older Street Fighter games who were still around at Capcom at the time, most of them were not on the Street Fighter 3 team. They had all the know-how, but they were all on the Street Fighter Alpha team. And the Street Fighter Alpha team and the Street Fighter 3 team never really shared much information with each other.

So by the time I came around, [the team] didn’t really have a very clear concept of what to do with the game. […] They had created a lot of animation patterns, and they wanted the hits to feel like they had a real heft behind them, to make it look cool when you took damage. But the problem was the team had no idea what kind of mechanics should go into the game in order to make it an interesting fighting game. There was no plan for that, and there weren’t enough moves for each character. So I ended up joining the team when the game was in that kind of state.

[Ed. note: Others point to a variety of issues slowing down development, some technical, as Capcom was working on new hardware and creating a game with a level of art and animation detail that was new for the company. Capcom declined an interview request with Sadamoto for this story.]

Takayuki Nakayama

(Street Fighter 5 director, Capcom Japan)

This project utilized the new CPS-3 board, which increased the number of colors that could be used for the characters from 16 to 64. Also, extra production effort was required to make the character animations more detailed. On top of that, the production of Darkstalkers was running simultaneously, making the initial team size small at the start of the project.

Akira Yasuda

(Street Fighter 3 artist, Capcom Japan)

I think [one] reason why development was so protracted was because of the lack of well-developed tools for the CPS-3 hardware we used for the game. One palette in the game could use up to 256 colors, right? But in order for us to exploit that palette, we needed tools that we just didn’t have. When developing for the CPS-3, we had to make a choice between having a high color count or having more pixels — a higher resolution, that is. When it came time for us to make that choice, we went with having a higher color count.

Chris Kramer

(Street Fighter series public relations representative, Capcom USA)

A month or two before I left [Capcom, localization manager Tom Shiraiwa] took me in a room and locked the door and showed me a tape of Street Fighter 3 test animation. He’s like, What do you think? Will this be successful in the U.S.? Will American gamers like this? […] And really, it was just like idle animation, or here’s Ryu on a stage jumping or punching, and stuff like that. And you could see how much more was going into the game, in terms of animation and movements, and the art style was definitely light years beyond Street Fighter 2. But it was always going to be a huge thing for them and they had to do it absolutely right. So I think they went through some stops and starts before kind of landing on what they eventually released. […]

It was hard to say [whether I thought it would be successful]. I think my initial feedback was, “It looks amazing.” He was like, Yeah. And told me, he’s like, Oh, this will be CPS-3 so we’ll have all new arcade hardware, and he’s like, They’ll never be able to do this for the PlayStation, because the PlayStation won’t be able to do all the animation correctly. So it’s really a showcase for the CPS-3 hardware and shows how important arcades are. Because that was always a big deal. The arcade guys always wanted to make the ultimate arcade experience, even though realistically, the line was like, Hey, put it out in the arcades. It gets popular and then six, eight months later, it comes home and then the sales explode from there. But the arcade guys were definitely always looking to showcase how they could do things at a high end of the scale, because it had infinitely more RAM than a home console did at that time. They could do a lot more clever stuff on their dedicated hardware.

Seth Killian

(Street Fighter 4 special combat advisor, Capcom USA)

SF3 was before my time at Capcom, so my only insight into why it might have been a long dev cycle is based on my general perspective as a developer who has worked on many fighting games. SF3’s sprite animation work is considered one of the finest achievements in the genre, but nothing about it scales. Because those animations are all carefully hand-drawn, and made by a shrinking pool of pixel-artist talent, even a small change to an attack might require redoing a lot of work, which slows down your ability to experiment and iterate. This is especially tough because SF3 probably needed to iterate more than any game in franchise history. The parry system was both very different from previous Street Fighter games, and also very delicate — a few frames in either direction could make it impossible to attack. Finally, in addition to the regular surprises you get during any game development, the decision to make it a Street Fighter title sets expectations that are both high and specific, which can be a hard place to work from creatively.

[Ed. note: Obata says that not all of the development challenges led to an extended timeline — some came with other issues.]

Shinichiro Obata

(Street Fighter 3 planner, Capcom Japan)

Another problem, in terms of the game balance, was that the balancing and adjustments for the characters were done by separate people, so the balance was all over the place. One person would design their character to be more traditional and Street Fighter-like, then another would do it in the Darkstalkers style. There was no unity. […]

Up to that point, all the Street Fighter 2 games — specifically, Turbo, Super Street Fighter 2, Super Street Fighter 2 Turbo, and, though it’s a different series, Darkstalkers too … almost all of the balancing — that is, how strong the characters are, how strong their moves are, the level design — almost all of it had been done by one person, an extremely skilled programmer named [Yasunori] Harada. He had been handling everything, but for Street Fighter 3, we changed it so that everybody would handle their own specific characters. There are pros and cons to that kind of approach.

[Ed. note: Ultimately, Obata says he saw the game make large strides over time, with features like super moves added late in development.]

Shinichiro Obata

(Street Fighter 3 planner, Capcom Japan)

The Street Fighter 3 team was passionate but full of very inexperienced people. But I think things started to pick up a bit when a guy named [Kazuhito] Nakai joined the team. He was a very knowledgeable programmer, so development kind of sped up at that point. I came up with the idea for the “super cancels,” where if someone does a hadouken and then you input a super right after that, it will cancel the move. That type of cancel was my idea, and Nakai was able to program it for me. So while that was going on, I also homed in on the blocking and the parrying aspects that needed implementation and polish.

Also, one more thing worth mentioning was that five to six months before the game’s development was completed, a game designer named [Hidetoshi “Neo G”] Ishizawa joined the team. He had worked on Street Fighter Alpha 2. He was my kohai, my subordinate employee, but he ended up joining the team and I think he was very interested in the parry system, so he focused most of his energy on adjustments and balancing for that system. Nakai and Ishizawa gave us a much-needed boost, and we were able to make the attacks and moves more fun and interesting, have better game balance, new systems, and so on. […]

The biggest takeaway from all this is that the team was very indecisive and really had no idea what they wanted to do early on in development. But the thing is, there was so much pressure from within the company and from other teams, because this was Street Fighter 3, right? You know, this was the sequel or what came after the legendary Street Fighter 2. So there was just no way this game would be allowed to fail, and the team themselves — they were feeling that pressure, but they also felt the sense of obligation to complete what they were trying to do. So there was a lot of indecisiveness. There was a lot of back and forth discussion on what to do. And eventually they figured out, Yeah, maybe we should do this, this, and that. But it took a lot of time for the team to gather its bearings.

Street Fighter 3: New Generation debuted with 10 new characters. Unfortunately for Capcom, the new cast (seen in the above character art from 3rd Strike) didn’t resonate with fans to the same degree as the classic characters.Graphic: James Bareham/ProSpelare | Source images: Capcom

The new generation

One of Capcom’s boldest decisions for Street Fighter 3 was to drop most of its established characters in favor of a new cast led by a new main character: a wrestler named Alex. While Capcom reversed course on producer Sadamoto’s initial idea to release the game as a new intellectual property, the game still ended up with 10 new characters alongside Ryu and Ken, shifting the balance considerably.

This proved controversial, both because fans were disappointed to see their favorite characters missing, and because the new cast didn’t resonate with players in the same way as the original roster.

Chris Tang

(Street Fighter 3 design support, Capcom USA)

They sent us documents [showing the characters to Capcom USA via fax]. My first reaction was like, OK … I was a really, really big fan of Capcom, and I thought they could do no wrong. And the first time I saw the character designs for Street Fighter 3, I didn’t think they were real. I thought this was some other game. The first time I saw Oro, I was like, Did something happen? Did they fire everybody? Does Akiman [Akira Yasuda] still work there, or what?

So I did not have a favorable opinion of the designs when I first saw them, especially when they were, like, in a black-and-white fax. But later on, we found out they had a lot of frames of animation. They were able to leverage that to make them kind of cool. But my impression of the designs was not that favorable.

Akira Yasuda

(Street Fighter 3 artist, Capcom Japan)

On previous projects I had a lot of input on how the characters were envisioned, but on Street Fighter 3, Sadamoto’s opinions were obviously a very big driving force on how the characters were eventually designed. I wanted more freedom, but I couldn’t veer too far from Sadamoto’s character designs. In most of the games I’d been involved in, people came to me for guidance on the designs, but Street Fighter 3 was Sadamoto’s show, so I was relegated to brushing up his original designs. […]

I remember being there to put pressure on the team to do good work. For some of the characters, I would set the basics of the design early on. I would give the team directions and so forth, and they would kind of take care of things on their own. When there were certain parts of the design that weren’t going well, I would step in and maybe fix up a few things, but I didn’t really have such a concerted involvement in the game.

Shinichiro Obata

(Street Fighter 3 planner, Capcom Japan)

If we’re talking about what Akiman did, I think he might have forgotten this, but originally, Ryu and Ken’s pixel art and animation were done by a different person. But that person hadn’t been able to produce those animations at the quality needed, so Akiman actually went back and fixed a lot of the issues. […] So, that’s why they hold up so well today.

James Chen

(Street Fighter series commentator)

It was interesting, because it was all new characters except for Ryu and Ken, and nostalgia is one hell of a drug, and so a lot of people were like, I don’t care about these new characters. What is Oro? Like, What is this? You know, it was weird. […] I know a lot of people didn’t like the game much at all, and […] I think it had to do with the fact that a lot of the returning characters didn’t come back.

Ken Williams

(assistant editor, Electronic Gaming Monthly)

The fact that they pretty much killed the cast [was a bummer]. It was like, Who are all these characters? I’m like, I’m still expecting to see the primary cast. Even if you age them, right? […] And Alpha is guilty of that too, because it spoiled us in that way, bringing a whole bunch of characters into the mix.

Shinichiro Obata

(Street Fighter 3 planner, Capcom Japan)

If you look at games like Street Fighter Alpha, Alpha 2, and Alpha 3, they sold very well. And as you already know, they had familiar characters like Zangief, Blanka, and E. Honda that the fans really wanted to see. Just having those legendary Street Fighter 2 characters was enough for those games to sell very well. But because Street Fighter 3 had started out as an entirely different game, they had a totally new cast of characters, which nobody liked. The problem was that the characters had very uninspired designs, and I would say they were quite strange in comparison. If you think about the fact that we moved on to the CPS-3 arcade hardware for this game, I think people wanted to see Vega, E. Honda, etc. created on that new hardware with the technology it offered.

Ken Williams

(assistant editor, Electronic Gaming Monthly)

Having all new main characters really threw me off on the storyline. I had no problems with any of the new characters, but having Alex be the new main guy, I was like, He’s never going to be my main, ever. That’s never gonna happen. […] Obviously, we were [doing] just fine with [Ken]. If Western [players] wanted a Western character, Ken was a Western character. He’s American. He’s an American character with Japanese blood or whatever. Whatever his heritage was.

Akira Yasuda

(Street Fighter 3 artist, Capcom Japan)

I think it was lacking characters with traditional martial arts styles like judo and karate. I mean, come on. To have a guy with stretchy arms and he’s an Indian yogi, OK, that’s believable; that’s recognizable. But a guy who’s just straight rubber … ? It’s like they were almost sci-fi. It didn’t really feel like an authentic Street Fighter game. I don’t think the game had characters that felt like they belonged in a Street Fighter game. I mentioned Necro [the character who stretches like he’s made of rubber], and I personally like Necro as a character, but that’s not Street Fighter.

[Ed. note: Asked if he thinks it would have been better had Street Fighter 3 remained an original property, so the characters wouldn’t feel out of place in the Street Fighter universe, Yasuda says he’d prefer another way of changing history.]

Akira Yasuda

(Street Fighter 3 artist, Capcom Japan)

Actually, if I had to change the past, I’d rather just not have worked on that game at all.

The closeout

When Street Fighter 3 hit arcades, it proved to be a tough sell. The game showed Capcom’s 2D animation at its best, which gave the series a fresh coat of paint and a distinct identity among other fighters. But it arrived sandwiched between Virtua Fighter 3 and Tekken 3, leading some players and arcade operators to disregard it. “The great mystery is why Capcom called this SFIII instead of leaving that honor for a more powerful and revolutionary 3D title,” wrote Next Generation magazine in its review.

Fold in the unrecognizable cast and the deep roster of other fighting games competing for attention, and many were quick to dismiss Capcom’s game.

Ken Williams

(assistant editor, Electronic Gaming Monthly)

I actually went to Capcom to look at it for the first time […] and it was a little awkward because I didn’t like it much. To be honest, I really didn’t. […] It was too slow. It didn’t play well. It felt more like a gag, parody version to me. It just didn’t play the same. […] It didn’t really feel like a Street Fighter game, is probably the most damning comment I could have probably made to them. Because it didn’t play the same. It really didn’t.

Seth Killian

(Street Fighter 4 special combat advisor, Capcom USA)

I thought it was beautiful. I was blown away by the animation and the obvious care that had been poured into the game. That said, while it felt like an exciting new Capcom fighting game, between few returning favorite characters and a parry mechanic that gutted SF2’s full-screen fireball gameplay, it didn’t feel much like a Street Fighter game to me. The mind games around parries created iterated rock/paper/scissors games that were exciting, but that felt closer to Virtua Fighter gameplay than SF2’s positional tug-of-war.

Chris Kramer

(Street Fighter series public relations representative, Capcom USA)

You can’t feel how Street Fighter 3 plays so differently from Street Fighter 2 just by looking at it. If you look at screenshots, you’re like, Well, I guess that looks better, but you don’t understand how different those games are until you actually get in and start playing them. I can’t play Street Fighter 3 at all. I can’t play that game. I’m useless. Even though it’s a joystick and six buttons, I can’t get anything in that game. Street Fighter 2, I still have the same ingrained muscle memory for that, and that didn’t really translate across into Street Fighter 3.

Brian Duke

(director of national sales, Capcom USA)

I just remember, once again, being rather disappointed that it was so similar in play [on the surface], and I think that’s the time that I went to Japan and […] they told me it was coming, and I was like, My God, guys. Why do you keep doing this? And that’s when they gave me the analogy of hitting a single or double rather than a home run.

Matt Atwood

(Street Fighter 3 public relations manager, Capcom USA)

For me, that was the time it felt like they’d done a bunch of revisions and put in some new characters — I just felt like that was a time when we were looking and going, in my mind, Is that one we need? […] I think you were starting to see fatigue.

James Chen

(Street Fighter series commentator)

For me, it was cool that there was a new Street Fighter. They finally hit the number 3, as the joke was. I do remember going to Southern Hills Golfland and playing in tournaments over there for the game. So it was cool that we finally got a new Street Fighter. And so, there was a little mini resurgence at that point, but the game wasn’t particularly balanced, and the parries actually turned out to be kind of too strong. It was a good resurgence for the fans of fighting games, but in terms of pop culture, in terms of appealing to the masses, it was actually not particularly successful.

Shinichiro Obata

(Street Fighter 3 planner, Capcom Japan)

I personally felt that the game was incomplete. You know, there were three versions of Street Fighter 3, and I think the first one in particular felt unfinished.

[Ed. note: When selling Street Fighter 3, Capcom knew it was facing an uphill battle, in part because arcade sales were struggling as console game sales were exploding. “It’s not going to be as big as Street Fighter II,” Funamizu told Edge magazine just prior to the game shipping. “The games market had real power at that time, it’s flat now by comparison.”]

Akira Yasuda

(Street Fighter 3 artist, Capcom Japan)

The initial version of Street Fighter 3 saw shockingly low sales. I remember seeing the numbers and just being really surprised at how the game just wasn’t selling. […] It felt like we’d created the worst-selling game ever at Capcom. It felt awful.

Remember when I had to point out the bad aspects of [Street Fighter creator Takashi] Nishiyama’s game Avengers back in the day? Well, Street Fighter 3 only sold maybe twice the number of copies as Avengers. Avengers sold around 500 copies, and I think Street Fighter 3 only sold 1,000. So I felt like I was experiencing the same problem that Nishiyama had faced a decade earlier.

Street Fighter 2 had sold 55,000. Street Fighter 2: Champion Edition had sold 75,000. And one unit cost 240,000 yen [roughly $2,000 in 1997]. Back then, just to compare, you had to sell 3,000 arcade units in order to be considered a success. Before Street Fighter and Final Fight, 3,000 units of an arcade game sold was considered a success.

When Final Fight came out, that sold 30,000 units, and then after that, Street Fighter 2 came out and sold 50,000 units. So the standard had gone up from selling thousands of units to selling tens of thousands of units.

[And Street Fighter 3 sold] 1,000. That’s terrible, right? I mean, it was terrible because look at how much we had invested into the game’s development.

Shinichiro Obata

(Street Fighter 3 planner, Capcom Japan)

Yeah, the game didn’t sell well. I think it cost around 1 billion yen [$8 million] to develop, which back in the day was a very, very high budget. I think in terms of profit and loss, it might have been around zero in the end. It might have been a zero-sum project. Just barely not incurring a loss for the company. When we released 2nd Impact and 3rd Strike, I think the overall project became more profitable at that point. I remember the producer at the time saying we were lucky that the game didn’t bring us into the red. But yeah, I don’t know if it only sold a thousand units. I imagine we sold a bit more than that.

So, you know, it used a CPS-3 board, and each unit cost 200,000 to 300,000 yen [$1,600 to $2,400]. For a single board, that was quite expensive. And so I think the president of Capcom at the time had wanted to sell 50,000 to 60,000 units, because that’s what Street Fighter 2 was able to sell. But of course, we weren’t able to make those numbers with 3, unfortunately. […]

I think worldwide, I’d guess it sold more than 10,000 units.

Brian Duke

(director of national sales, Capcom USA)

It definitely was not more than 10,000 [in North America]. I guarantee you. It may not have been 1,000. It may have been 2,000. But I don’t think that we moved that many. In fact, if I remember correctly, I think that’s one of the few games that we did a closeout on, and it was all because we had [excess] inventory.

Chris Jelinek

(vice president of sales, Capcom USA)

Closer to the 1,000, from what I remember, than the 10,000. Not anywhere near 10,000. Nowhere near. I mean, unless they produced that many and dropped them in the ocean somewhere. No, it didn’t do 10,000 units. […] I’m thinking worldwide. [I worked in North America but] I had visibility to it.

[Ed. note: Former Capcom Coin-Op sales manager Drew Maniscalco estimates that Capcom sold 300 units of Street Fighter 3 in the U.S. “Overseas, I’m sure it was much better,” he says. Multiple former sales reps say that Capcom’s biggest arcade game of that time in the U.S. was Marvel vs. Capcom, which Maniscalco estimates sold 3,000 units.]

Chris Jelinek

(vice president of sales, Capcom USA)

I wouldn’t blame it so much on the game, although you can attribute some of it to the game. I mean, they were subtle iterations. But I think the big thing is that the arcades had just taken such a hit, right? […] Even the machines in places like 7-Elevens and all of that were getting pulled, right? So there was a complete shift as people expected that same experience at home.

Bill Gardner

(president and CEO, Capcom USA)

Would I say it was a disappointment? Only in the sense that all of coin-op was a disappointment [at that point]. […]

I just remember that [Capcom founder and CEO Kenzo] Tsujimoto was very upset. He would scream and pound the table when we had our monthly meetings because sales weren’t where he expected them to be, but he was looking at it from a totally different perspective. He was looking at it from the past.

So when I first joined the company, coin-op was so much bigger than consumer. Just, a number of times bigger. And they were selling a lot of coin-op over here. That was the mainstay of the Capcom business, was coin-op.

And, you know, they made, and they still do make a lot of money on coin-op in Japan. So as Street Fighter 3 came out, the home console business was starting to really take off. I mean, really take off. And so when we made our monthly reports in Japan, we’d go over and I’m reporting on a million-unit seller on home console, right? And coin-op was going and saying, “Well, we sold 450 units this month,” or something like that, you know? And Tsujimoto was just — he was beside himself. He was convinced they weren’t working, and he wasn’t quite in touch with the revolution that was taking place.

[Ed. note: Capcom declined an interview request with Tsujimoto for this story.]

Shinichiro Obata

(Street Fighter 3 planner, Capcom Japan)

I feel like Street Fighter 3 was one of those projects where just a bunch of unfavorable results came together into one game. […] If we had had good leadership and followed a clear vision from the beginning, I feel like it would surely have been a hit.

By the time Capcom released Street Fighter 3: 3rd Strike, it had brought back four legacy characters — Ryu, Ken, Akuma, and Chun-Li — to fight alongside its army of 16 newcomers.Graphic: James Bareham/ProSpelare | Source images: Capcom

Delayed redemption

Despite Street Fighter 3’s slow start, Capcom continued to invest in the series with follow-ups 2nd Impact and 3rd Strike. The new versions brought back beloved legacy characters Akuma and Chun-Li, and refined many of the series’ mechanical and balance issues. While neither of the entries reached the sort of commercial success Capcom had seen in the early ’90s, both went on to earn significant critical acclaim, with 3rd Strike in particular becoming a cult favorite.

Over time, Street Fighter 3’s reputation shifted — what was once a series that many felt was behind the times because it couldn’t match 3D standards went on to become appreciated as a rare premium 2D game.

Shinichiro Obata

(Street Fighter 3 planner, Capcom Japan)

After the game came out, Capcom had a postmortem regarding what worked with the game and what didn’t, and they realized that the design needed to be put into the hands of an experienced designer. So that’s why [Hidetoshi “Neo G”] Ishizawa became the lead designer of the project and took it forward. […] The end result of that is 3rd Strike. 3rd Strike was made under his careful direction.

Takayuki Nakayama

(Street Fighter 5 director, Capcom Japan)

I do think [3rd Strike] was a turning point for the series. The return of Chun-Li, the inclusion of characters that are popular to this day like Q and Makoto, and updates done to the controls and blocking system leading up to this title made this a significant release. I think it also helped that players were able to improve their skills over the two years since the release of the original.

James Chen

(Street Fighter series commentator)

You know, even though a lot of people talk about how 3rd Strike is, like, This is the pinnacle of Street Fighter. This game is so great — when that game came out, nobody cared. Like, it was just the same thing again. Chun-Li was clearly overpowered, and a lot of people were really mad about that. You could just hit back heavy punch all day, and it just killed half the characters in the game, and nobody really cared. So a lot of people have this assumption that Street Fighter 3: 3rd Strike came out and just resurrected it. Nowadays everyone talks about it as this gold standard. But honestly, during that time, nobody really [batted] an eye on it. It was not that popular of a game in the arcades.

Seth Killian

(Street Fighter 4 special combat advisor, Capcom USA)

The difference between [3rd Strike and New Generation] was mostly just time. It’s no accident that the best Street Fighter games in a series tend to be the last ones. Developers understand their own systems better over time, and in conversation with their most dedicated players. There’s almost no debate among those core players that 3rd Strike was the best of the SF3 series, but there was also no magic ingredient — 3rd Strike is just a beautifully refined game. Its interest is limited to a small group of experts, but the magic of parries made it feel like glorious victory was always just one good read away, even for the game’s many underpowered characters. That’s intoxicating.

Shinichiro Obata

(Street Fighter 3 planner, Capcom Japan)

It’s also worth mentioning that Street Fighter 3 is not a casual-friendly game. So if you don’t really know the technical aspects of the game, you might be trying to attack and getting blocked, or if you try to cancel but it doesn’t do what you intended to do, then you can get confused if you’re a casual player. Street Fighter 3 was a very technical game, and I think in that sense, professional players like it a lot and it’s a game that they have enjoyed for 10 to 20 years at this point. […]

You know, there are many different approaches you can take to game design. One approach, which we took in SF3, is to design your game around “unanswerables.” I think with any game, players will search for the best tactic, the best strategy … like, if X happens, you should always do Y; if you do this here, you’ll always win. There’s competitive games like that, where the match is essentially a confrontation of theoretical knowledge that each player has built up. But Street Fighter 3 is a game that, by design, doesn’t have a fixed answer to those questions. There is no “best” tactic; you can spend your whole life trying to find the perfect theoretical approach to a situation in SF3, but it will never be quite right. You always have to be reading your opponent in the moment; you can’t just fall back on your theories. It’s a game that lets you search for answers forever. And that was the opposite of Street Fighter 2.

We have changed certain game titles and character names throughout this series to reflect their English versions and reduce confusion. Job titles reflect past roles relevant to the topics discussed.

Japanese interview interpretation: Alex Aniel

Post-interview retranslation: Alex Highsmith